THE PUBLICATION RECENTLY OF A BRIEF ARTICLE in the Platypus Review touting Lenin’s ideas in Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism is an apt occasion for scholars of Marxism-Leninism to return to that text for a fuller examination of its contents.1 The book appeared in 1916 at a low point in Lenin’s political fortunes. The prewar agrarian reform program of prime minister Peter Stolypin had darkened the prospects of revolution in Russia. Endless factional disputes during these years had plagued Russian revolutionary politics. Lenin had looked increasingly to Western Europe as his primary source of hope for revolution, anticipating that the imperialist rivalries of the great powers could produce a crisis pregnant with revolution. Lenin had not long to wait for his analysis to be confirmed.

World War I created on a gigantic international scale conditions that in a smaller and more localized version had followed the Russo-Japanese War ten years earlier. That war had been fought for imperialist objectives as well. Most European socialists became patriots after 1914, but Lenin vigorously promoted a policy of revolutionary defeatism, hoping to turn what he called the imperialist war into a civil war. Lenin’s assessment of the war’s causes in Imperialism mark it as the least original of his major works. In the preface, he sought to deflect criticism by blaming the book’s shortcomings on his need to circumvent the Tsar’s censors. A more serious intellectual liability arose from the wholesale use he made of John Atkinson Hobson’s Imperialism: A Study (1902). Hobson, a British economist and journalist, had argued that imperialism functioned simultaneously as a safety valve for capitalism and as a source of international conflict. Lenin, acknowledging his large debts to Hobson, followed essentially the same line of argument and used Hobson’s data to illustrate it as well. By pushing the argument with polemical gusto to Marxist conclusions that the social-democratic Hobson did not share, Lenin made vital contributions of his own. After the Bolshevik revolution, Imperialism would become a canonical text on the European Left as the definitive Marxist explanation of the real causes of World War I, but Hobson gave the book its research base and general thematic orientation.

Lenin intended his book to be a composite picture of the world capitalist system in which he sought to prove that “the war of 1914–1918 was imperialist (that is, an annexationist, predatory, war of plunder on the part of both sides).”2 He charged that “the tens of millions of dead and maimed left by the war” had been sacrificed on the altar of capitalist imperialism.3 To the lost generation of 1914, Woodrow Wilson’s slogan about fighting a war to make the world safe for democracy seemed obscene in a postwar aftermath defined by the imperialist transactions solemnly carried out at the Paris Peace Conference. For many who had emerged from the carnage with their prewar values shattered, Lenin’s explanation of what the war was really about made far more sense. The war, Lenin had written in 1916, was “to decide whether the British or German group of financial plunderers [was] to receive the most booty.”4 Lenin had proposed to scrub away, with his Marx and Engels, the cosmetics that the masters of capitalist cosmetology had applied to the hideous face of the war. The Treaty of Versailles and the other settlements following the war lent credence to his interpretation of that conflict as a conspiracy for capitalist imperialism.

In the last half of the nineteenth century, the world economy had entered a stage that Lenin called “monopoly capitalism.” Enormous industrial growth, accompanied by the rapid concentration of production in larger and larger enterprises, defined the monopoly capitalism of that era. A financial oligarchy with unprecedented power and influence had come into being. Lenin noted that even bourgeois critics such as Hobson had expressed alarm about “the monstrous facts concerning the monstrous role of the financial oligarchy.”5 The system had produced enormous profits, but, as always under capitalism, the purpose of wealth was to gain more wealth for the investing classes, not to raise the living standards of the masses or to improve their lives in any meaningful way.

Despite the inherently exploitative nature of the capitalist system, some sections of the proletariat in Western countries, Lenin conceded, had derived economic benefits from the new monopolistic order. Hobson — “a most reliable witness, since he cannot be suspected of leaning towards Marxist orthodoxy”— gave him the necessary clue to understanding the true worth of those benefits.6 In Imperialism: A Study, Hobson had described the exceptionally parasitic attributes of the new imperialism, under which profits that were unprecedented in their bloated volume were being extracted from colonized territories in the non-Western world. Lenin, basing himself on Hobson’s research, concluded, “The world has become divided into a handful of usurer states and a vast majority of debtor states.”7

Lenin fully shared Hobson’s fears about “a European federation of great powers which, so far from forwarding the cause of world civilization, might introduce the gigantic peril of Western parasitism, a group of advanced industrial nations, whose upper classes drew vast tribute from Asia and Africa, with which they supported great tame masses of retainers, no longer engaged in the staple industries of agriculture and manufacture, but kept in the performance of personal or minor industrial services under the control of a new financial aristocracy.”8 For the time being, the war had derailed the possibility of a “United States of Europe.” The system had not been able to contain its competitive energies, but Hobson had been right, Lenin argued, to worry about the potential for such a European federation under monopoly capitalism.

Some of the elements for a Western-dominated new world order had already been in place when the war changed everything. Lenin singled out the prewar decline of the revolutionary movement as one of those elements. Reformists all over Western Europe had corrupted the working-class movement. He had mainly in mind Eduard Bernstein, whose Evolutionary Socialism (1899) had been the chief object of his fury in What Is to Be Done? (1902).The high monopoly profits accruing from the partitioning and exploitation of the non-Western world made it possible to “bribe the upper strata of the proletariat,” thereby fostering, encouraging, and strengthening Bernsteinian rationalized opportunism.9 Lenin continued, “Imperialism has the tendency to create privileged sections also among the workers, and to detach them from the broad masses of the proletariat.”10 Marx and Engels had displayed their usual acumen by noting how in England the working class had very early developed along reformist trade union lines rather than in the direction of revolution precisely because of the British Empire.

Lenin thought that the mid-nineteenth-century British example of workers battening on the misery of the non-Western masses had become more generalized. Now the same process could be observed in America, Germany, and Japan. He could see no fundamental differences among any of these capitalist countries. They all were doing the same thing, despite differences in outward political trappings: “[I]n all these cases we are talking about a bourgeoisie which has definite features of parasitism.”11 Yet, he claimed, “the intensification of antagonisms between imperialist nations for the division of the world” had caused the thieves to fall out among themselves.12 “If the forces of imperialism had not been counteracted, they would have led precisely to what [Hobson had] described.”13 The war had counteracted them, and it had created the opportunity for revolutionaries to redirect the course of history.

In Europe, Marxist opinion about imperialism has come down predominantly from Lenin. To the radical European Left, his 1916 book was a sort of urtext. For example, Amadeo Bordiga and Antonio Gramsci, two key founders of the Italian Communist Party in 1921, discovered in Lenin’s Imperialism and other writings the full meaning of imperialism in the contemporary world.14 This was a typical discovery by postwar European Communists. Stalin furthered the cult of Lenin in the Soviet Union. From the late 1920s to the early 1950s, Stalin’s influence would pervade the entire Communist world. A book that Stalin had written in 1924, Foundations of Leninism, summarized the principles and historical outlook of what would become known as Stalinism. This book would become the main repository of doctrinal purity for Communists during the Stalin era.

Stalin cited numerous works by Lenin, but Imperialism made the deepest impression on him, as the point of departure for understanding the global depredations of the world’s capitalist power structures. He derived three fundamental theses from Lenin’s analysis of imperialism: First, the parasitic nature of monopoly capitalism had created the preconditions for proletarian revolution. Second, capitalism had been transformed dramatically from a national system into a world system of financial enslavement and colonial oppression. Third, the relentless imperialist struggle for control of the world had made possible the conjoining of “the front of the revolutionary proletariat and the front of colonial emancipation,” i.e., the downtrodden workers in the advanced countries of Europe and the subject peoples of the non-Western world.15 Lenin’s profound book fully explained how all the evils of the Great War had been caused by the viciously exploitative imperialist order conceived and nurtured by monopoly capitalism.

In the writings of journalist John Reed, America could boast of having a premier Bolshevik of its own. Reed’s paean to the Bolshevik Revolution, Ten Days that Shook the World, appeared in 1919, with a glowing introduction by Lenin himself, who wrote of the book: “Unreservedly do I recommend it to the workers of the world.”16 He said he wanted it to become the official history of the Bolshevik Revolution. Reed described the book in the preface as a “chronicle of those events which I myself observed and experienced.”17 He did not pretend to be writing a clinically objective account of the revolution. “Adventure it was, and one of the most marvelous mankind ever embarked upon, sweeping into history at the head of the toiling masses, and staking everything on their vast and simple desires.”18 With a charismatic power that entranced Reed, Lenin furnished the indispensable communist corrective to the peasant and worker-slaying capitalist status quo that had America, under the sanctimoniously viperous Woodrow Wilson, as its new enforcer. Lenin, according to Reed, possessed “the power of explaining profound ideas in simple terms, of analyzing a concrete situation.”19 In Imperialism, he had given Reed a dialectical way to think about his prewar and wartime reporting in Mexico where the banking and business interests of the United States and their local adjutants had kept the miserable peons in an iron cage of capitalist exploitation. Lenin had laid out for him the inner workings of how the world functioned as a prison system for the wretched of the earth.

Reed, however, did not set the trend for the reception of Leninism in the United States. There, the Communist left led a fretful existence. Overwhelmed and ghettoized by the Red Scare of the 1920s, Communism in America never approached the political or intellectual importance that it achieved in Europe. Yet, insofar as Lenin had derived his ideas from Hobson, the argument in Imperialism entered the mainstream of American liberal and social democratic thinking. Charles Austin Beard, the chief conduit for this transfer of knowledge from Europe to America, had met Hobson in England at about the time he was writing Imperialism: A Study. While a history graduate student at Oxford, Beard spent most of his time engaged in working-class reform work. In that way, he entered the orbit of the social democratic Left where Hobson shone as a presiding luminary. Hobson’s book made no less of an impression on Beard than it did on Lenin.20About the causes and effects of imperialism, Lenin and Hobson held virtually identical views, while differing about how to combat it, either through revolution or reform. The core ideas of Imperialism influenced American thought primarily through Beard’s adaptation in his hugely influential work, through their original formulation in Hobson.

Beard had read Marx and found much to admire in him, but his main ideological starting point had consisted of a systematic reading of John Ruskin’s philosophically conservative social criticism. Ruskin’s Unto This Last (1862), the foundational book of Beard’s youth, belonged to the conservative anti-capitalist intellectual tradition, which had been championed in the previous generation by Thomas Carlyle, whose Past and Present (1843) made a sufficiently favorable impression on Friedrich Engels, then living in England, for him to recommend it to his future collaborator Marx. Engels acknowledged the hopelessness of Carlyle’s conservativism as a way out of the capitalist inferno, but he insisted that Past and Present deserved careful reading for its vivid critique of the status quo in England. From these Carlyle/Ruskin beginnings, Beard came to Hobson, who also found the classics of the philosophical conservatives — Ruskin most of all — eminently worth reading as a supplement to his leftwing views about politics and economics. Under the influence of Hobson and like-minded intellectuals in England, Beard too became a social democrat in his general worldview, while always retaining an enormous admiration for Ruskin’s moral and aesthetic indictment of the capitalist order as the blight of the world.

Returning to the United States in 1902, Beard completed a history Ph.D. at Columbia. When barely out of graduate school he began to write about imperialism from a strict Hobsonian point of view. As Beard entered the Progressive movement, soon becoming one of its star intellectuals, he continued to tout Hobson’s book as an analysis indispensable for understanding the meaning of imperialism and the economic forces behind it. Hobson’s way of thinking about the indissoluble connections between government policy and powerful economic elites became the germ of his thought as a historian. The book that made Beard the most famous and controversial historian in America, An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (1913), conformed to the general viewpoint he found in Hobson.

One of the mysteries of Beard’s career concerned the reasons in 1914 for his uncharacteristic support of American intervention in the Great War. In expressing such support, he repressed everything Hobson had taught him. It is a complex story, involving, among other factors, his strong sense of cultural and ethnic affinity with the British, the seductive power of the first-class propaganda campaign to which Americans were subjected, and his entirely misplaced faith in the cause of fighting a war to make the world safe for democracy.21

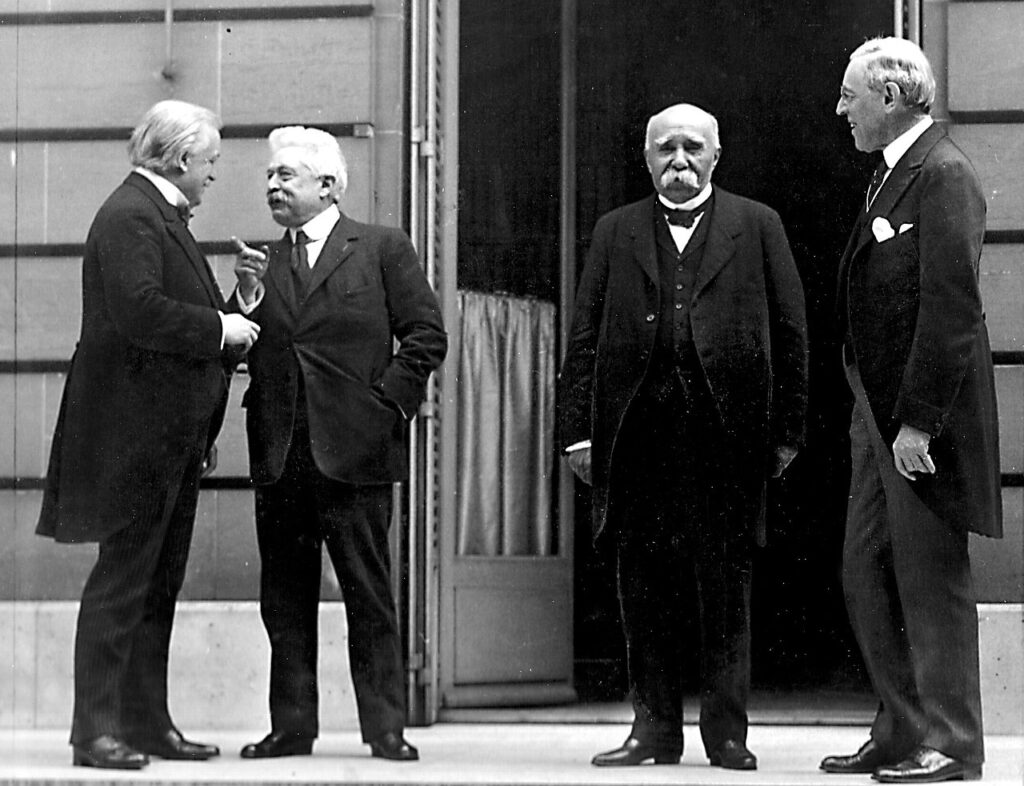

One look at the Treaty of Versailles, however, made clear to Beard the real reasons for the war. He swiftly and permanently returned to the Hobsonian fold. The war, he now realized, had been fought for the tangible benefits of empire: the markets, resources, and territories of subject peoples. Beard, as one of the most famous historians in the world for An Economic Interpretation and a leading public intellectual in his own country, became a powerful spokesman in the revisionist movement, which enjoyed great success during the interwar period in advancing an interpretation of the Great War fundamentally in keeping with Hobson’s ideas about imperialism and the conflict itself.22 Other thinkers during this period contributed to Beard’s understanding of the Great War’s imperialist character, most notably Brooks Adams in The Law of Civilization and Decay (1895), another classic in the tradition of philosophical conservatism — but the Hobsonian core of his writing on imperialism always remained in evidence.David Lloyd George, Vittorio Orlando, Georges Clemenceau and Woodrow Wilson at the Paris Peace Conference

Beard, who was in sympathy with the isolationist movement though not a member of it, opposed FDR in the run-up to American intervention in the Second World War and thought of him as a kind of Wilson on steroids trying to make America both the engine and the shield of corporate capitalism worldwide. When Beard persisted, even after Pearl Harbor, in his view that all capitalist wars were exercises in empire building, he made serious enough enemies with the powers-to-be to do him reputational harm. He still had an enormous following, and his books continued to sell phenomenally, but the guild of professional historians by and large turned against him, and his influence in the scholarly world dwindled. By opposing the “good war,” Beard had committed the unforgiveable sin against the Holy Ghost.

William Appleman Williams and the Wisconsin School of historians kept the legacy of Beard alive in American historical scholarship. Williams, who was more sympathetic to Marxism than Beard had been, in his works The Tragedy of American Diplomacy (1959), The Contours of American History (1961), and Empire as a Way of Life (1980) attributed imperialism to the country’s economic elites who, along with the regnant political class, controlled policy-making in Washington. In the first of these books, he extolled the democratic potential of Marxism, which, he said, “can be described as totalitarian only by falsely isolating and dramatizing one of its particular facets.”23 He conceded what he called “the brutal and undemocratic aspects of the Bolshevik Revolution” and the terrorist enormities of Stalin.24 Yet, by insisting that Stalin was not Hitler, Williams “disdained the totalitarian thesis about Marxism-Leninism and opened for Beardians the question of Lenin’s legacy.”25 He called that legacy a complex one and concluded, “This review of Russian experience suggests that the sources of Russian conduct are the drives to conquer poverty and to achieve basic security in the world of nation states.”26 At the height of the Cold War, he faulted the United States for focusing on the evils of communism instead of the evils that attracted peoples to it: poverty, hunger, and racism. The tragedy of American diplomacy lay in its failure to stand for true human freedom. American leaders had confused freedom with a licentious regime for global capitalism.

For the final edition of The Tragedy of American Diplomacy (1972), Williams continued to condemn the exploitative foreign policy of the United States but harshly criticized the shortcomings of Soviet and other communist leaders for the invasions of Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968, adding, “but to concentrate exclusively on these points is to neglect others of considerable importance.”27 It still seemed to him that the benefits of communismcould not be dismissed. Less than six months before his death in 1990, Williams tried to set the record straight with regard to his attitude toward Marxism. In a letter to James W. Groshong, a retired faculty member from the English Department at Oregon State University where Williams had taught for many years after leaving the University of Wisconsin, Williams declared, “Obviously, I consider myself a Marxist: no apologies and no denying the problems inherent in all that.”28 He did not identify with the activist branch of Marxism, but, on balance, thought that “intellectual Marxism offers the most insightful mode of perceiving the world and, as an intellectual, making sense of the world.”29 The leading members of the Wisconsin School among his students did not follow him into the socialist camp.30 From this perspective, in his own school of thought of Marxist ideas, Williams was an outlier. With regard to Lenin’s Imperialism, he clearly accepted its main argument, but as it had been presented earlier by Hobson through Beard.

It was Beard, not Marx, who had given Williams the main pointer he needed to understand the actual course of American history. He described this lesson in Contours as Beard’s “great and unforgivable transgression” in recognizing that the country’s oligarchy stood in permanent opposition to the aspiration for a democratic society.31 Beard had shown how throughout American history, private and group interests had triumphed over the common good. In American parlance, the idea of the common good expressed in anything but the argot of capitalist salesmanship seemed vaguely threatening, as if someone’s money bags might be at risk of expropriation. Political leaders were not groomed to promote society’s general development; rather, “leadership became instead a task of representing a specific element of the system and attempting to secure its objectives through conflict and compromise with the other elements.”32 The point of a system encouraging every man to gain the utmost was for some of its members to get rich, not to build a sober democratic community. Williams called the American people to a polity of self-discipline and sharing as the only way of ridding themselves of the militarism and imperialism corrupting the nation. Only by changing their habits and outlook could they dismantle the American empire — as Beard, more clearly than any other historian, had foreseen.

Beard belonged in the front rank of the critics identified in Empire as a Way of Life as that “impressive and delightfully variegated group of Americans who created the tradition of speaking truth to empire.”33 Beard had performed the most thorough examination of America’s imperialist past and present, demonstrating how at every crucial turn in American history, economic elites had achieved the policy outcomes conducive to empire. For Williams, “empire became so intrinsically our American way of life that we rationalized and suppressed the nature of our means in the euphoria of our enjoyment of the ends.”34 He called this legerdemain a process of reification. The historical education furnished in Beard’s books held the promise of leading Americans to a higher plane of understanding about the manner in which and for whose benefit their country worked.

A lingering question for today concerns the uses to which the Hobson-anchored legacy of Beard and Williams can still be applied with regard to current foreign policy issues in the U.S. The 2020 election has turned out the Trump administration which had promised to introduce fundamental changes in American foreign policy. In the 2016 campaign, Trump distinguished himself among Republican presidential candidates for denouncing the Iraq War as the terrible mistake it was. In office, he has been given credit as being the first U.S. president in 40 years not to start a new war — though not for lack of trying. The hit on General Qassem Soleimani in January 2020 in Baghdad — and Trump’s bellicose policy toward Iran in general — might easily have kept the American presidency’s “new war” militarist record intact. With equal facility, relentless interference in the affairs of Venezuela could have accomplished the same objective. Meanwhile, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as the American-aided horrors in Yemen, have remained ongoing throughout the years of the Trump Administration. The surreal Defense Department budget and related military expenses remain an object of envy for militarists in foreign lands who can only fantasize about a uniquely munificent military-industrial complex of their own. The logic of empire has determined U.S. foreign policy during the Trump era.

The incoming Biden administration is unlikely to bring any fundamental changes to the foreign policy status quo. As with Trump in 2016, Biden the presidential candidate in 2020 presented himself as a critic of the war in Iraq. He professed to have learned from his mistake in having supported that conflict in 2003. Moreover, Biden let it be known that, in the Obama administration, he had opposed the decision in 2011 to attack the regime of Muammar Ghedaffy in Libya, a country ever since overwhelmed by chaos and also a prime source of the immigration woes fueling rightwing populist movements in Europe. These encouraging signs of repentance and independent-mindedness notwithstanding, any hope that Biden might be an agent of serious change in the foreign policy establishment did not survive news of his appointments of Antony Blinken as secretary of state, Lloyd Austin as secretary of defense, Jake Sullivan as national security advisor, and Avril Haines as director of national intelligence. These individuals all have long records of service implementing the policies designed to protect and defend the global corporatist status quo. The business of foreign policy will be conducted at the same old stand.

Hobson made a prophetic pronouncement toward the end of the First World War about the manner in which the corporate capitalist establishment from then on would carry out its plans. He argued, “All the intellectual and moral as well as the financial resources of the ruling and possessing classes that hate and fear democracy (though doing lip service) will be used so as to control and dope public opinion as to prevent the formation and emergence of a popular will reasonable enough to master the state, and through the state to reform property, industry, and social institutions.”35 He might have added foreign policy to this list of reforms. For ferocity, treachery, falsehood, and pitilessness, the battle waged by the oligarchy would be unlike any other in history, and it would be ongoing. It has not ended yet. In launching a debate about the requirements for a democratic foreign policy, the Hobson/Beard/Williams legacy is worthy of critical examination.

This article first appeared in Platypus Review 133 | February 2021

Be First to Comment